FBF #10: The Hidden Cost of Straight A's

Five ideas about how grades stifle curiosity and hinder intellectual growth.

Academics have always been my drug of choice. When I was in first grade, I received the Scholarship Award at the end of the year. Ever since I’ve been chasing that dopamine hit of the A (or increasingly ubiquitous A+). And I think that’s a damn shame.

Grades do have some positives. Just like capitalism, they at least theoretically reward hard work and clear understanding. They provide an easy-to-understand, quantitative measure of our academic prowess. When coupled with thoughtful comments, they work fairly well.

But their drawbacks are numerous. The existence of grades transforms education into a transactional process, where the winners are the ones who are best at gaming the system. They reward “book smarts” and often deaden intellectual curiosity.

“Good” students pursue top marks with a monomaniacal fervor that would make Captain Ahab proud. I almost never field questions from a student who scored in the 70s, but God forbid you give that academic overachiever a 97, and they will fight tooth-and-nail for a 98.

Home Depot is My Waterloo

The only C I ever got on my report card was in sixth-grade woodshop. The effects of this “failure” (to take a page out of my daughter’s distorted lexicon) have been pervasive. To this day, trips to Home Depot are my Waterloo and DIY projects make me question my masculinity. I can usually manage to put together IKEA furniture with only a handful of missteps, but tackling home improvement projects that require me to measure and figure things out on my own terrify me. And I believe it all goes back to that woodshop class that convinced me that I was no good with my hands.

And this brings us to the crux of the issue. Students base their entire self-conception on their GPA, a number that looms so large in childhood and yet has never, as I remind my students, made it into a eulogy or onto a gravestone.

What follows are five reflections on the place of grades in education today:

1) Breeding Ground of Fixed Mindsets

There is a subtle but insidious way that grades sap strong students from reaching their potential. For a student who has always done well, the prospect of getting a bad grade is such an abject horror that many resort to moral shortcuts like cheating when faced with difficult material. Their self-perception of being a good student is so important to protect that they are afraid to explore new things or to ever be a beginner. Grades are the breeding ground of fixed mindsets that cripple students and prevent them from taking risks.

The need to do well academically prevented me from pursuing passions that would have served me well in the long term. I fled from anything STEM-related at Harvard, afraid these courses would hurt my academic average. As a result, even now I am maddeningly incurious when it comes to science, irrationally fearing that my foundation is too shaky to understand complex ideas.

I credit Mr. Engel, my ninth-grade English teacher and advisor, with making me fall in love with literature, vocabulary, and the written word and to ultimately follow in his professional footsteps. He used to tell me I could write better than half of the faculty. But his inflated belief in me had a soft underbelly. Because he had applauded my talent, I felt I must always perform. When an essay was assigned, dark storm clouds rolled in because I knew an all-nighter the night before the deadline was in store for me.

James Clear shared a great quote in yesterday’s edition of his 3-2-1 newsletter, which he touts as “The most wisdom per word of any newsletter on the web.”

Success in school does not have a one-to-one correlation to success in life. I have taught plenty of students who did not excel academically. But I am nevertheless sure will thrive in the real world because of their grit and focus. And then there are other students, myself included, who have been held back by success on their report cards.

2) Can We Grade Our Soul?

My school has a curious line item on our official transcripts called “Daily Spiritual Audit.” The source of this measure is the daily muhassaba, an accounting checklist that students must fill out every day to assess their spiritual practices. It consists of more than 20 questions like the one below in which they are supposed to indicate how closely their daily practices hew to the Prophetic routine.

While the intention of this activity is undoubtedly sincere, the mere mention of the word muhassaba triggers a Pavlovian response of fear and apprehension in many students. While some credit this activity with dramatically improving their Islamic practice by motivating them to embed many sunnas into their daily routine, many others bristle at being “graded” on their spiritual practice and say that attaching the external motivation of grades to religious rituals robs them of sincerity.

I probably fall into the latter camp as I prefer to be my own worst critic in private. I have always been attracted to the inner dimensions of Islamic spirituality, and this scorecard technique of checking off external practices would likely prove counterproductive for me.

I’m not sure what college admissions officers think when they see “daily spiritual audit” on the transcript, but I suspect that we are one of the only schools in America that seeks to grade the soul.

3) All Work and No Play Makes Jack a Dull Applicant

College admissions is at least in part to blame for our grade- and achievement-obsessed culture. But students and parents fundamentally misunderstand the role of grades in college admissions. Grades or board scores might open the door to the top 20 schools, but they alone will NEVER push you through it. Every year Harvard and Yale gleefully boast about how many high school valedictorians and students with 1600s on their SATs they have rejected.

Many immigrant parents are relentless in browbeating their children about grades. This obsession clips their children’s wings and prevents them from developing in other categories that are heavily weighted in “holistic” admissions decisions. Many Muslim parents cling to the outdated notion that the only two paths to worldly success are engineering and medicine, and they are horrified when their son/daughter expresses an interest in journalism or the arts.

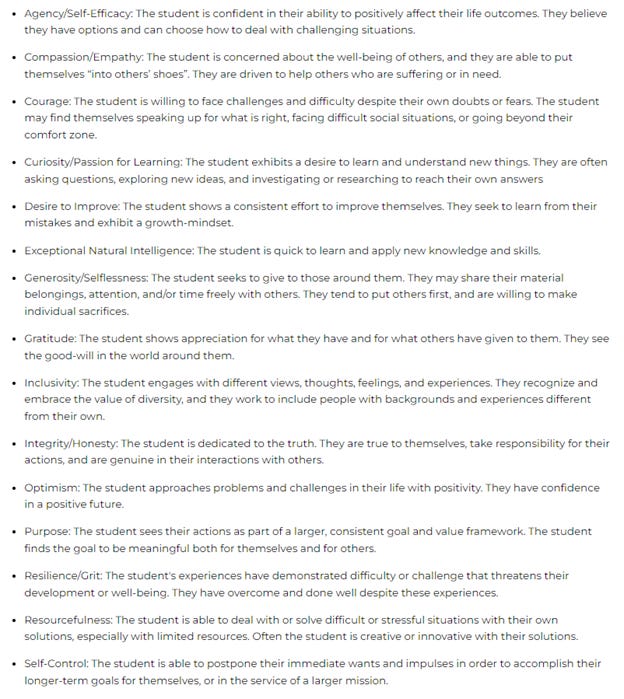

QuestBridge, an amazing non-profit that connects high-achieving, low-income students with top-tier colleges and universities through a national college match program publishes an illuminating list of the criteria they most value when evaluating students. Notice how many of these focus on EQ over IQ.

4) Failure is Only a Dirty Word in School

Failure is something that our schooling teaches us is a mortal sin. Yet the workplace and life in general seem to reward failure. Those who have been bruised by falling short have developed calluses that help them push on when things look bleak. As Sahil Bloom phrases it in his excellent article, the Grit Razor states that “if forced to choose between two people of equal merit, choose the one that has been punched in the face.”

Infographics like this one abound on LinkedIn:

There are countless aphorisms that pay homage to the concept of “failing forward.” Here are five:

a) “Don't fear failure. Not failure, but low aim, is the crime. In great attempts it is glorious even to fail.” -Bruce Lee

b) “Failure should be our teacher, not our undertaker. Failure is delay, not defeat. It is a temporary detour, not a dead end. Failure is something we can avoid only by saying nothing, doing nothing, and being nothing.” - Denis Waitley

c) “Failure is the condiment that gives success its flavor.” - Truman Capote

d) “Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.” - Winston Churchill

e) “Failure isn't fatal, but failure to change might be.” - John Wooden

While paeans to failure have become so common as to sound trite, these are messages that we need to consistently reinforce with our children.

5) Is There Another Way?

Last weekend, I was fortunate to return to Brattleboro, Vermont for an impromptu reunion of my 2005-2006 MAT cohort at the School for International Training (SIT) which I consider to be my academic Valhalla.

My year in the foothills of southern Vermont was magical. I had just gotten married, and the honeymoon glow brightened my mood. But, more than that, SIT was different. The faculty focused on experiential learning, and they modeled the same student-centered approach in their own teaching that they were encouraging us to adopt.

I learned about the mystical Silent Way from Shakti Gattegno who explained that “knowing the right answer is sometimes the greatest impediment to learning” and “getting it wrong is part of getting it right.” I came to believe that “the teacher must not do for his students what they can do for themselves” and that the greatest accomplishment a teacher can achieve is to cede the responsibility for learning from his shoulders to those of his students.

But the biggest innovation and gift of SIT was that there were no grades, only thoughtful comments. The absence of grades spurred in me an intrinsic motivation that made me compete only with myself, and I realized that I often had higher standards than my teachers. I often tell people that I got more out of one year at a graduate institute few have ever heard of than I did from four years at Harvard. This comment smacks of my trademark Henshaw hyperbole, but it contains lots of truth.

If I were being graded on these Five Before Five newsletters, I probably would have never begun. Or at least I would have been petrified and taken three times as long perfecting them. And that would have been a damn shame.

As a homeschooler, I have seen first hand what pursuing a love of learning looks like. We don't have grades and our kids are allowed to study what interests them. Isn't this what learning is supposed to be? I agree with you wholeheartedly that grades stymie the best of intentions. I wish schools could somehow get rid of grades and just let kids learn for the sake of learning.

I do think it is crucial to grade our souls, but not with letter grades. Ideally, at the end of every day, we should take ourselves to account. Were we kind? Did we say anything we regret? Some of my most precious, Muslim female teachers made us take ourselves to account since one day we will be taken to account by the Lord of the Worlds.

Thank you again for these very important thoughts! Always the best part of my week! :)

Also, below are some interesting links and questions about the Growth mindset and the importance of being ok making mistakes, which teachers and parents can share with their children/students:

Questions:

a) Why does having a growth mindset or fixed mindset matter in mathematics/statistics, and do you think you have a growth mindset or a fixed mindset? How do you know?

b) How does your own experience of learning mathematics/statistics connect to the idea in this video?

c) What is one thing that is mentioned in this video, which you will implement in this class this semester, and potentially other classes?

d) Anything else that you found insightful/interesting about the video(s)?

-------------------

Video1:

Study Skills - Make Mistakes by Michael Starbird

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2yYQ-1X2ocU

Video2:

The Power of Not YET by Carol Dweck

Video3:

Grit by Angela Lee Duckworth

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H14bBuluwB8

Video4:

Sal Khan interviews Carol Dweck on Growth Mindset

https://youtu.be/wh0OS4MrN3E

Video5:

Michael Jordan about "Failure"

https://youtu.be/JA7G7AV-LT8

Video6:

Growth Mindset Animation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-_oqghnxBmY

Video7:

Four Boosting Messages

https://www.youcubed.org/resources/four-boosting-messages-jo-students/