Five Before Five #4: Building Central Park into Our Day

A weekly newsletter blending insights from western thinkers with the evergreen wisdom of Islam

Before we get into this week’s newsletter, I wanted to share a podcast episode that I recently recorded on Meli Solomon’s Living Our Beliefs podcast. It was a wide-ranging and productive discussion about my conversion to Islam, professional journey from finance to education, and the development of Islamic schools in the States. Enjoy, and please let me know what you think!

Take Advantage of Your Free Time Before Your Busy-ness

The fourth portion of the beautiful five before five hadith exhorts us to, “Take advantage of our free time before our busy-ness.” After we have taken care of our youth, and our health, and our wealth, what’s left? Our free time.

Most of us have designed our lives in a way that affords us very little free time. Between sleeping, working or studying, and fulfilling other necessities, there are only a few hours left each day. We tend to use this extra time to pursue mindless leisure activities such as social media and Netflix marathons, which do not usually lead to significant personal growth.

I often tell my students that how we choose to use our free time will determine how we will spend our eternal lives in the Hereafter. It will also go a long way towards determining how fulfilling our lives will be in this world.

Before we get into strategies for maximizing the amount of free time we have and discussing how to best use it, let’s first talk about the opposite of free time: busy-ness. Western society fetishizes busy-ness. When queried about how they are doing, almost everyone gives some variation of “Man, so busy” or “Crazy busy!” We wear it almost like a badge of honor that screams, “I am important.” As Tim Kreider explains in his fantastic NYTimes op-ed The ‘Busy” Trap, these responses are just boasts disguised as complaints.

Busy-ness is a self-imposed affliction, mostly impacting the affluent, that is primarily rooted in anxiety. Most people feel guilty when they are free, seeing it as a stain on their character that shows they somehow lack ambition and drive. What’s worse, we have passed on these same values to our children, overscheduling them with extracurriculars that will “look good on college applications.”

Those of us with jobs that require us to be in the office during set hours are probably keenly aware of how much of our time is wasted by minutia. It brings to mind the brilliant scene in Office Space in which Peter Gibbons, when asked by a consultant to walk him through a typical day, responds:

“Well, I generally come in at least fifteen minutes late, ah, I use the side door - that way Lumbergh can't see me, and after that I just sorta space out for about an hour… I just stare at my desk; but it looks like I'm working. I do that for probably another hour after lunch, too. I'd say in a given week I probably only do about fifteen minutes of real, actual, work.”

The work-from-home lifestyle necessitated by the pandemic opened our eyes to the vast swathes of free time that we could earn if we structured our professional lives differently. Probably the single best thing we can do to increase our stockpile of free time is to negotiate to work from home at least twice a week.

But now that life has mostly returned to normal, busy-ness has crept back into our lives. We are again drowning under the weight of urgent tasks that are usually not very important, using our claims of being too busy as an existential hedge against leading a meaningless life.

The primary thesis of this piece is that we need to claw back and store up as much free time as we can and then jealously guard it against incursions. The question remains as to why? Tim Kreider explains it in the most compelling language I have heard:

“Idleness is not just a vacation, an indulgence, or a vice: it is as indispensable to the brain as vitamin D is to the body, and deprived of it we suffer a mental affliction as disfiguring as rickets. The space and quiet that idleness provides is a necessary condition for standing back from life and seeing it whole, for making unexpected connections and waiting for the wild summer lightning strikes of inspiration—it is, paradoxically, necessary to getting any work done.” (Lazy: A Manifesto)

If any of us is feeling stuck or burned out, we should ask: Have we left ourselves enough breathing room to just be still and to reflect? How much time do we devote on a daily or weekly basis to self-improvement, pet projects, and just generally tapping into our creative genius?

One of my favorite exercises in the classroom is to show a picture of New York City from above. The size of Central Park is breathtaking. Surrounded on all sides by the frenetic energy of the city that doesn’t sleep, Central Park is an oasis of green that helps keep people sane. Imagine the trillions of dollars that could be had by building commercial real estate on top of the park. But, thanks to the vision of Frederick Law Olmstead and the foresight of urban designers, Central Park is a permanent fixture in the city.

We must build our own Central Park into the architecture of our daily lives. The more ambitious and hungry we are for success both here and hereafter, the more stringently we must protect our free time. Several times each week, we must set aside inviolable blocks of unstructured time that no Zoom call, email, or meeting can interrupt.

Now I want to share some specific strategies for stockpiling free time and then suggest a few ways to productively use it.

1. Say Hell Yeah! or No

I have lost count of the number of high-powered guests on various podcasts who have credited Derek Sivers’ manual of this title for allowing them to wrest back control of their calendars. The idea is that early in our careers, when we are scratching and clawing our way towards achieving a foothold in the professional world, we say yes to nearly every opportunity that crosses our plates. “Will you speak at an event six months from now? Sure.” “Can you travel to Copenhagen to meet our CEO? Why not.” Over time, however, we need to develop a better heuristic for deciding which opportunities to pursue and which to ignore. Sivers’ simple answer: if we don’t find ourselves saying “Hell, yeah!” then we should ALWAYS say, “No.” Filling our schedule with meetings, excessive travel, and speaking engagements is the death knell of the sorts of deep work and thinking that actually make a difference.

2. Audit our Free Time

Very few people have ever done a careful accounting of their time. It is very hard to optimize your schedule for free time until you collect the data about where you are already spending it. One simple way to get a snapshot of how we are spending our digital time is to go to “screen time” on our phones and then look at the specific categories and apps that provides tangible (and often depressing) evidence about where we spend our time online.

But it is critical to get a picture of how we use our entire 168 hours, the title of a book by Laura Vanderkam that my wife is currently reading. The two best methods to do this hour-by-hour accounting are old-fashioned pen and paper or an app like Toggl Time.

Once we have the data, we should categorize our free time and use the Pareto principle to figure out what 20% of our time is yielding 80% of our results. We should then do three things:

a) Invest more time into those critical 20% activities.

b) Cut down on the 80% activities as much as possible.

c) Block out a significant portion of our saved time for idleness.

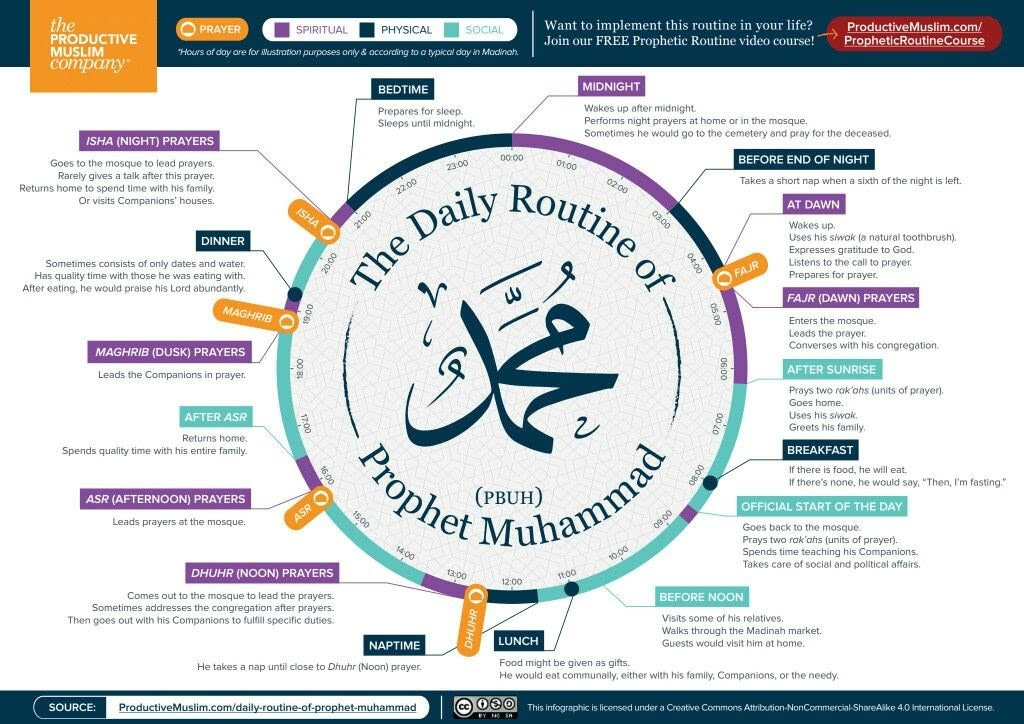

3. Adopt a Prophetic Routine

One of the beautiful aspects of Islam is that it builds the perfect daily, weekly, and annual schedule for us. If we simply strove to recreate the time management system of our beloved Prophet (PBUH), we would have no need for time audits. This poster of the Prophetic routine, created by the Productive Muslim Company, is one of the most profound time management tools I have ever seen.

As we can see, the five daily prayers provide regular breaks to re-connect with our purpose and the Divine. On a weekly and annual basis, Jummah prayers and Ramadan are systemic practices built into the faith designed to help us recharge our imaanic batteries. Once we have carved out free time, be sure to invest it in improving our commitment to the deen.

All Muslims should adopt a daily “wird” of religious practices, no matter how small, that they can stick to consistently, bearing in mind the two hadith of the Prophet (PBUH):

“Take up good deeds only as much as you are able, for the best deeds are those done regularly even if they are few.” (Ibn Majah).

“The most beloved of deeds to Allah are those that are most consistent, even if they are small.” (Bukhari).

Here are five practices I recommend:

a) Fajr in the Masjid:

This is the cornerstone of my day. Getting up early, making the sacrifice of going to the masjid, beginning the day with remembrance of Allah. What could be better?

b) Daily Quran

Whether it is a few ayahs after every salah, a page a day, or the ideal—one juz’ per day—having a consistent routine with Quran is mission critical.

c) Morning and Evening Adhkar

It is said that the angels are changing shifts during the time after Fajr to sunrise and the time after Asr until sunset. Try to set aside this time for the beautiful morning and evening adhkar. Our school uses Zoom to have the entire student body do the morning adkhar together.

d) Read at Least One Hadith a Day

Designate a salah (Isha is a popular choice) to read and reflect on at least one hadith a day from a book like Riyad al-Saliheen or Muntakhab Ahadith. Do this with your whole family, and watch it transform your lives.

e) Visit or Call Someone Once a Week Purely for the Sake of Allah

There is a hadith that says:

“Verily, Allah will say on the Day of Resurrection: Where are those who love each other for the sake of My majesty? Today, I will shelter them in My shade on a day when there is no shade but Mine.” (Muslim)

When we visit one another with no ulterior motive but to please Allah, it builds love and connection and strengthens the community.

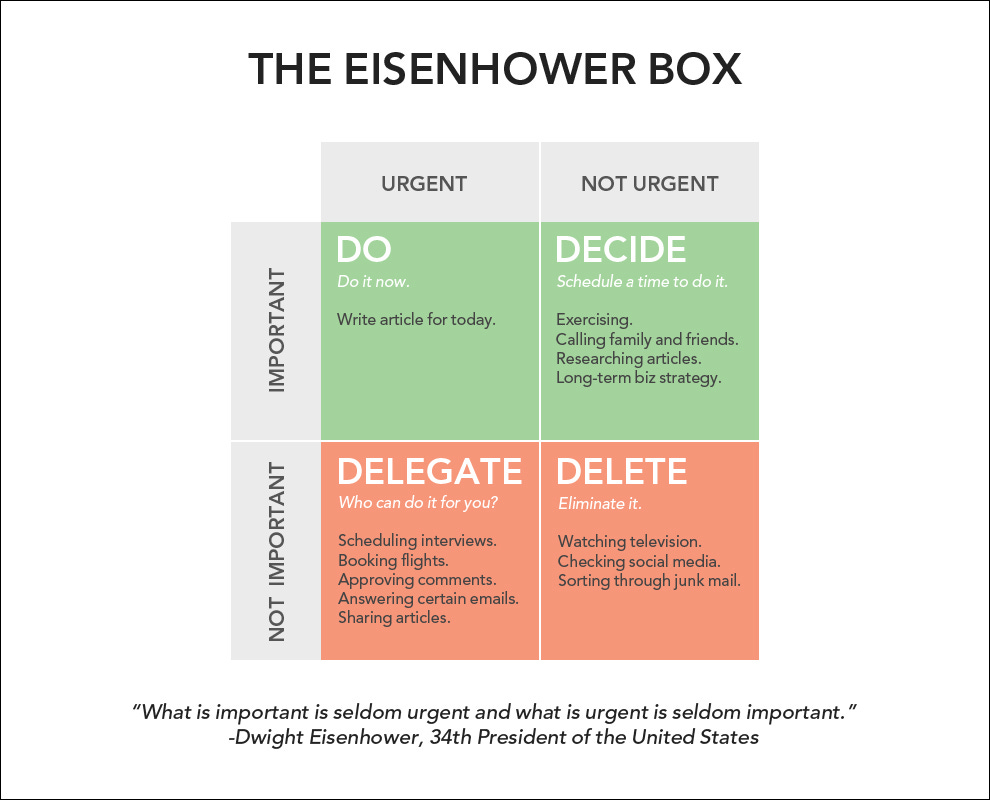

4. Use the Eisenhower Box

This technique, invented by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, is a productivity mainstay that was featured by Stephen Covey in his famous Seven Habits of Highly Successful People. While articles like this one from one of my favorite newsletters, Sahil Bloom’s Curiosity Chronicle, can provide more comprehensive details, the main idea is that we should use this matrix to categorize our activities.

By deleting the unimportant, non-urgent tasks and delegating the urgent ones, we free up time to focus on the important. The biggest takeaway of this exercise is that we must SCHEDULE time to focus on those non-urgent yet important tasks that so often are casualties of our busy lifestyle. Setting aside time to write this newsletter is an example of how I am trying to use this matrix to help make more productive use of my free time.

5. Find a Hobby

This one probably sounds simple, but it is remarkable how many people have so overstuffed their lives that they have no time left to pursue hobbies. It is very difficult to make friends as adults, yet I have built up an amazing network of friends over the past 10 years by pursuing two of my most cherished hobbies: tennis and pickleball. Walking, as covered in FBF #2, is my other main hobby. But other ideas include: gardening, smoking meat, pickup basketball, fishing, geocaching, reading, collecting. Really the possibilities are endless once you prioritize the stockpiling of your free time.